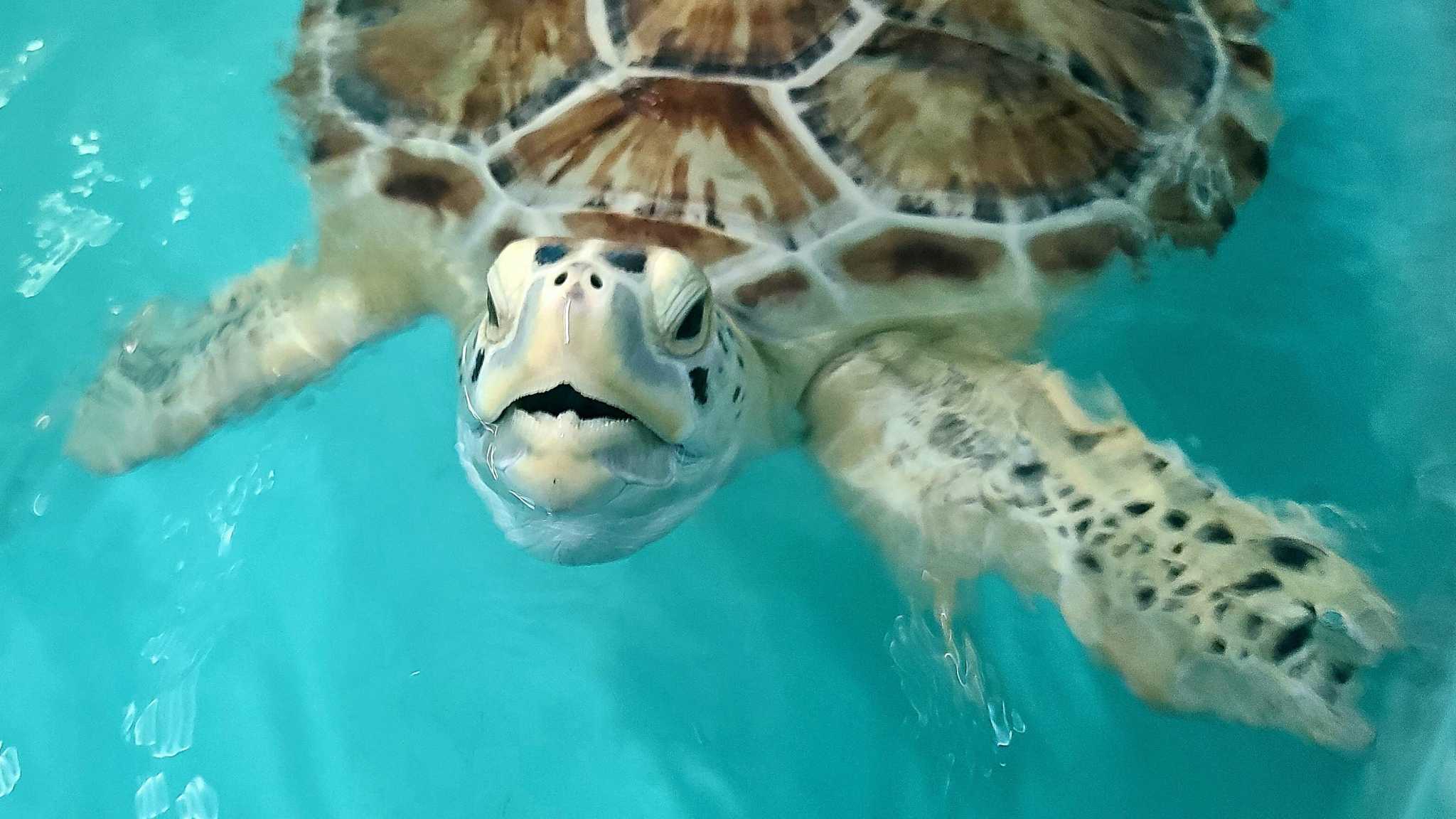

This organization researches and helps protect the highly endangered Kemp's Ridley sea turtle - Houston Chronicle

A group of sea turtles peers over Seawall Boulevard, and the Gulf of Mexico beyond, from a mural on the side of Galveston's McGuire-Dent Recreation Center. The Turtles About Town statues, created by the Turtle Island Restoration Project and Clay Cup Studios, serve as 50 further reminders of the island city's — and the public at large's — fascination with these seafaring reptiles.

"There's something about sea turtles that people just love, and I'm so surprised at how much people are thrilled with sea turtles," says Christopher Marshall, director of Texas A&M University at Galveston's Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research.

"I think it has to do with the fact that they're just so ancient," he says. "They seem like they've been here — well, they have been here — for millions of years, and people recognize that. There's something special about something so ancient and primitive still swimming our seas and following those primal urges to come up onto the beach and lay their eggs and return back."

Southeast Texas is home to five of seven sea turtle species in the world, including green turtles, loggerheads and the highly endangered Kemp's ridley, the official sea turtle of Texas. The center was established in 2019 to coordinate research between scientists around the region and promote conservation activities, including public awareness, on behalf of an animal that until not so long ago was on the brink of extermination in this part of the world.

The Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research relies upon sources of support through sponsored research, grants, gifts and donations. To donate to the Sea Turtle Hospital Fund or purchase a Texas Sea Turtle Specialty license plate, visit tamug.edu/GulfCenterforSeaTurtleResearch.

Therefore, according to Marshall, the center's primary focus right now is simply trying to get a handle on the local turtle population.

"What we're trying to do is answer the questions 'who's here?' in terms of the species: how many of them are here and at what stage of life history are they here — basically, are these juveniles, subadults, or adults?" he says. "All those are important for proper management of sea turtles in our area."

One thing Marshall does know, sadly, is that Texas' turtle population took a significant hit from February's winter storm, though thousands more were saved. But the more A&M's researchers learn about the animals' environment, the more they can help protect them. They're currently focusing on a "mark and recapture" program where they outfit turtles with electronic tags similar to what veterinarians use to keep track of household pets.

They also glue a device to the turtle's shell that employs a satellite uplink, another tool to help measure their range. In turn, this helps his team understand more about turtles' habitat and foraging needs, Marshall says.

"They're using all parts of Galveston Bay, even way up into Trinity Bay," he says. "We've had several turtles up into the higher reaches of Galveston Bay, as well as the adjacent coastal waters. And so all of the Galveston Bay estuary system is important to our sea turtles."

Learning how turtles use the bay can also have a ripple effect, Marshall says. Agencies like Texas Parks and Wildlife and the Galveston Bay Estuary Program can use the center's data to identify "a habitat that can be set aside and protected for sea turtles — but also all the other marine community that's associated with those habitats, too," he says.

"Those sea turtles are not an apex predator by any means, but there's a whole other community of animals that live in sea grasses and oyster beds," Marshall adds, "so sea turtles are kind of like a flagship species that can protect whole ecosystems."

Additionally, the center is running point on an areawide turtle rescue program, housing sick and rescued turtles until they're ready to return to the wild. (The Houston Zoo helps provide veterinary care.) It recently launched a fundraising campaign to build a much larger hospital and education outreach center, where visitors will be able to watch turtles being rehabilitated, learn about marine conservation and greet the resident "turtle ambassadors."

If all goes well, says Marshall, doors could be open in 2024. "The idea is to generate ecotourism dollars to sustain our conservation programs," he says. "It'll be a real tourist attraction on the A&M campus."

Assisting Marshall's team are dozens of volunteers, such as Carlos Rios, who describes his first sea turtle encounter as love at first sight.

"You get your hands on a sea turtle for the first time and you're like a little kid going goo-goo ga-ga," he says.

Rios retired from the Houston Chronicle in 2007 after 30 years as a photographer. He got involved in A&M's Texas Master Naturalist volunteer program, which funnels trainees into either land management or endangered species. He chose the latter and worked for a long time with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Galveston facility before coming over to Marshall's center when it opened last December.

His duties include going on "turtle patrols," where he and other volunteers comb Galveston's beaches looking for nests.

It almost never happens, but a couple of years ago, he actually saw a turtle come out of the water and nest on the beach.

When they do find a nest, researchers and volunteers remove the eggs and send them to a sister facility on South Padre Island, where hatchlings are periodically released into the sea.

Rios has seen that, too. Lately, he's been working at the "turtle barn," the center's rehab hospital, where he cleans the tanks and helps prepare meals. He took a special liking to a patient named Stubbs, whose flippers had to be partially amputated and battled serious illness for weeks before improving. She was medically cleared and scheduled to be released last month.

"I got to the point where I could get her to come up to the side of the tank and scratch her back, and she'd do a little turtle dance for me," Rios says. "Those are those little moments that you have with some of these turtles that you're not supposed to humanly befriend, but you do have this connection with. There's kind of a magic that goes on with that."

Chris Gray is a Houston-based writer.

Comments

Post a Comment